Urban AirQ:

citizens measuring air quality themselves

10 August 2016

Who’s really the boss in our city? The mayor? The corporations? Or us—the citizens? Gradually, cities are becoming ‘smarter’, more efficient, and more intertwined with technology. Building ‘Smart Cities’ seems to be the solution to all our problems.

But who defines what those ‘problems’ are anyway? And who designs the solutions? What happens to the data collected? These are questions that we ponder in our quest to design solutions for modern urban problems.

Earlier this year, we started a pilot programme within the EU programme, Making Sense, which placed citizens in a position to measure the air quality in their own backyards, streets, and neighbourhoods. In collaboration with GGD Amsterdam, the KNMI, the Long Fonds, Wageningen University, and ECN Netherlands, we rolled out a programme in which citizens cooperate with experts and worked together for several months while learning how to measure their environments with low-cost technologies. With the help of expertise and the (available) official measuring stations, inexpensive sensors could be calibrated to produce reliable data.

The beginning

Thanks to a targeted recruitment campaign in and around the Valkenburgerstraat & Weesperstraat (the two most polluted streets in Amsterdam), an enthusiastic yet worried group of around 25 residents gathered in the Waag. During these evenings, participants were introduced to experts in the field of air quality and the available technologies for measurement. During those early meetings, plans of attack were forged—by the residents themselves. They decided what they wanted to measure and why. And the questions they asked were quite diverse. One resident wanted to know how his street fared when compared to the high street’s pollution levels. Another was more interested in the difference between air quality in the back garden versus the front stoop. From that starting point, 16 sensors were distributed among the participants.

The sensors

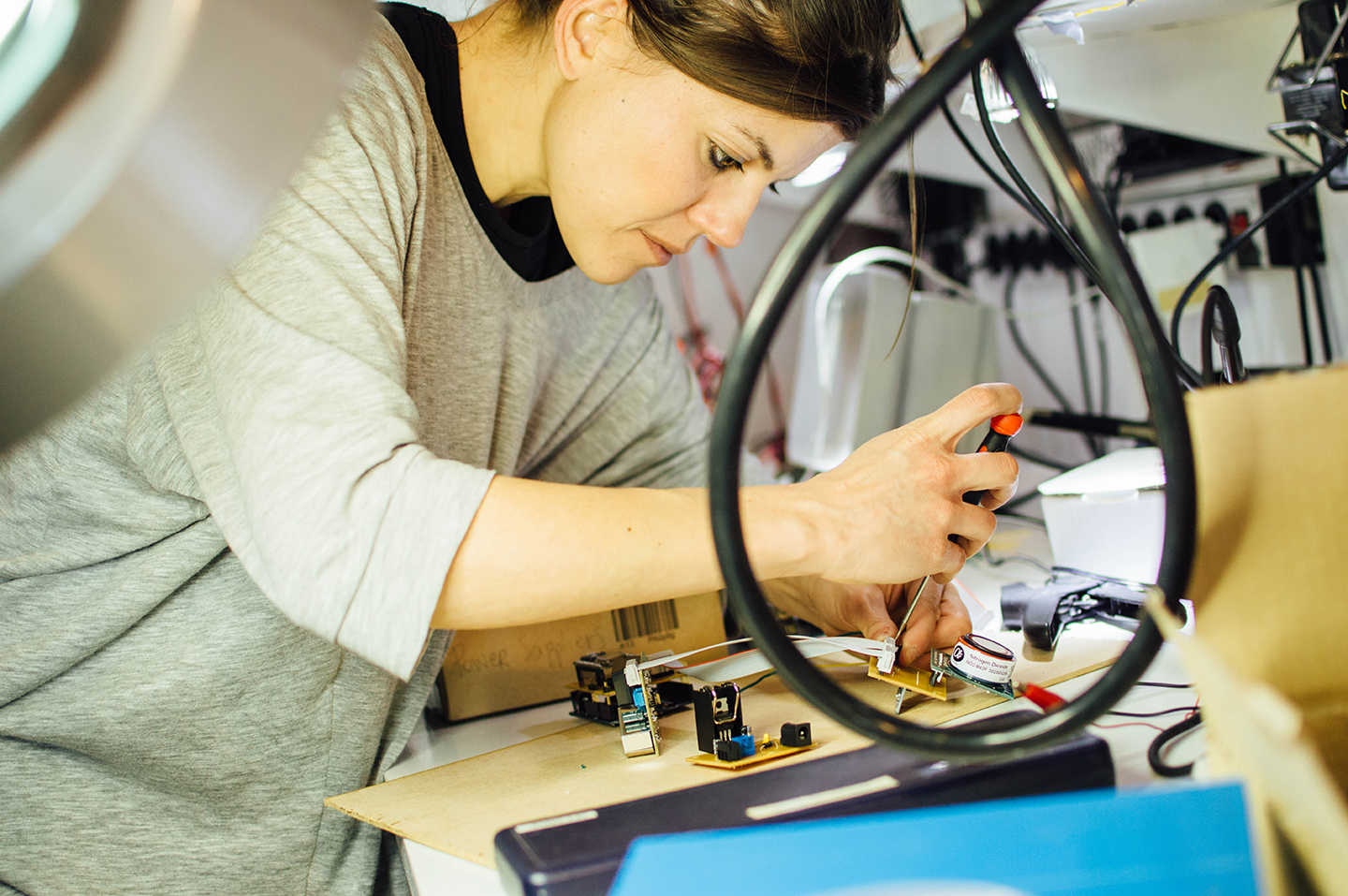

The hardware we use for the project is an air quality sensor built upon some previous designs. Hardware from a previous pilot in 2014, the Smart Citizen Kit, did not yield the data that participants expected yet. Another sensor, developed in close collaboration with Wageningen University and RIVM during last years’s edition of the Amsterdam Smart Citizen Lab was a good starting point. This base was reproduced, adapted, and updated with some better sensors (e.g. the NO2 sensor). The sensors were connected to the participants’ Wi-Fi networks and now measure: NO2, particulate matter, humidity, and temperature. The live data from the participants’ devices can be seen here.

The participants

Many participants take part in the programme out of concern for the quality of life in their city. The simple fact that they can measure the quality of their day-to-day environment is often enough to awaken their enthusiasm.

So this is also a group of local residents who, outside of this project, are often active concerning the liveability of their city and neighbourhood. An example is Jet Willers. She is worried about the pollution from taxis circulating through her relatively quiet street to pick up customers from the Red Light District and Nieuwmarkt at night.

Another example is Ria Teeffelen. She would like to know whether or not it’s safe to sit outside the front of her house. For comparison, she has hung a sensor both on her front stoop and in the back of her house—where she has a lovely courtyard. With this data and new information, she can now make an informed choice about where to sip her coffee.

Where are we now?

The sensors were hung in mid-June and they will stay up until midway through August. So, we’re currently halfway through the measurement period. Interestingly, the IJ Tunnel will close at the end of this week. This may make for some noteworthy differences—especially in and around the Valkenburgerstraat, which opens directly onto the tunnel. The participants currently have the ability to access their realtime data via a simple web application. However, it should be mentioned that this is still an experimental technology, so we can’t draw any major conclusions just yet.

What’s next?

We will continue measurements over the coming months. Once the test period is over, the data will be analysed with the help of the KNMI. Hopefully, this analysis will provide some conclusions and help answer some of the participants’ questions. The whole process is, in any event, a nice experiment to see what sort of data quality can be obtained from these low-cost sensors and how we can connect experts with residents to identify problems and improve quality of life.

Ultimately, this experiment will contribute to our goal of “open technology”. So the project was designed and structured with this goal in mind. Thus, through this project, we become a little bit more like the bosses of our own city.